Remember when dinner out meant something? When steakhouses weren’t just places to eat but destinations where memories crystallized over sizzling platters and endless salad bars? These vanished temples of beef tell stories more complex than any Michelin star could capture, much like the famous hamburgers that vanished from fast food menus across America. You’re about to journey through the graveyard of American steakhouse dreams, where each shuttered sign represents not just failed business models, but the evolution of how we dine, dream, and spend our Friday nights. From chains that fed millions to regional legends that defined entire communities, these restaurants shaped decades before disappearing into that great dining room in the sky.

13. Wags

Walgreens’ restaurant division proved that retail synergy doesn’t guarantee dining success. Wags combined steak dinners with American comfort foods, conveniently located near pharmacies where families could grab prescriptions and dinner in one stop. The concept seemed logical—captive customers, established locations, corporate backing.

But running restaurants requires different expertise than selling toothpaste. Divided corporate attention between core pharmacy business and restaurant operations led to inconsistent execution. The complexity of food service ultimately diverted focus from Walgreens’ main competency, proving that diversification can dilute rather than strengthen brands.

12. Valle’s Steak House

Donald Valle’s 1933 creation epitomized elegant dining when restaurants were special occasion destinations. White tablecloths, extensive banquet facilities, and prime rib that could feed armies made every meal feel celebratory. The chain expanded to 30 Northeast locations, becoming the go-to choice for anniversaries, graduations, and business dinners that mattered.

High operational costs and changing dining preferences eventually overwhelmed Valle’s traditional approach. The shift toward casual dining in the 1980s left white-tablecloth concepts struggling to justify premium pricing when competitors offered similar food in relaxed atmospheres. Valle’s represented a lost era of dining grandeur that modern efficiency couldn’t sustain.

11. Mountain Jack’s Steakhouse

Founded in 1979, Mountain Jack’s created lodge-style intimacy with tableside salad service that made every dinner feel personal. Cozy atmosphere and attentive hospitality set it apart from competitors focused on volume and efficiency. Prime rib became the signature dish, drawing customers who valued quality over quantity and service over speed.

High overhead from full-service operations and competition from national chains with deeper marketing pockets ultimately proved unsustainable. The personalized service model, while beloved by customers, couldn’t compete economically with streamlined operations that achieved similar satisfaction at lower costs.

10. Sirloin Stockade

Oklahoma City’s 1966 gift to family dining perfected the buffet-steakhouse hybrid for middle America. Families could satisfy everyone from picky toddlers to teenage bottomless pits with endless buffet options alongside quality steaks. Western-themed decor created atmosphere that was both comfortable and slightly exotic for suburban diners.

Competition from larger buffet chains and changing health consciousness eventually eroded the customer base. Quality control across numerous buffet stations while managing rising ingredient costs proved increasingly difficult. Handful of franchise locations survive in smaller markets where the concept still makes economic sense.

9. York Steak House

General Mills’ 1966 experiment brought cafeteria-style efficiency to steakhouse dining, primarily in shopping malls where convenience mattered more than ambiance. Dark wood and red carpeting created surprisingly intimate atmosphere despite assembly-line service model. The concept proved quality beef could be served quickly and affordably.

Mall-dependent locations suffered as shopping patterns changed and customer expectations evolved toward full-service dining experiences. Many of these restaurants eventually joined the growing number of abandoned malls across America, victims of changing retail landscapes. The cafeteria service model, once innovative, felt increasingly dated compared to competitors offering traditional table service without significant price premiums.

8. Hilltop Steakhouse

Some restaurants serve food; others become mythology. Hilltop Steakhouse, with its 68-foot neon cactus beckoning drivers from miles away, achieved the latter. Frank Giuffrida’s 1961 creation in Saugus, Massachusetts, could seat over 1,000 people and did so nightly, serving 2.4 million customers annually during its peak. The place was less restaurant than phenomenon—a beef-serving machine that somehow maintained soul despite its industrial scale.

But size became Hilltop’s fatal flaw. Single-location restaurants can’t achieve the economies of scale that chains use to survive downturns, yet they carry enormous fixed costs. High overhead, changing tastes, and the impossibility of modernizing such a massive operation led to its 2013 closure. Hilltop’s demise illustrates the restaurant industry’s cruel irony: becoming too successful can make you too big to survive.

7. Beefsteak Charlie’s

All-you-can-eat shrimp, unlimited beer and wine, and a salad bar that stretched like a small grocery store—Beefsteak Charlie’s didn’t just serve dinner, it served abundance wrapped in old New York charm. The chain embodied the excess of the 1980s, where getting your money’s worth meant eating until your pants protested. Those Tudor-style interiors echoed with the sounds of celebration and the occasional groan of overindulgence.

The unlimited promotions that drew crowds ultimately demonstrated the fatal flaw in loss-leader strategies. When your signature offerings cost more to provide than customers pay, growth accelerates losses rather than profits. Quality suffered as costs spiraled, creating a death spiral that closed most locations by the early 1990s. Beefsteak Charlie’s became a cautionary tale about the difference between perceived value and actual sustainability.

6. Sizzler

Nothing said “family night out” like the sound of steaks hitting those signature hot plates, accompanied by the sweet siren song of an all-you-can-eat salad bar. Founded in 1958, Sizzler democratized the steakhouse experience, proving that families didn’t need white tablecloths to feel fancy. The formula was simple: affordable protein, endless salad, and the kind of reliability that made it every suburban parent’s backup plan.

But Sizzler exemplified the restaurant industry’s most dangerous trap: the mushy middle. As dining polarized toward either fast-casual efficiency or elevated experiences, Sizzler’s middle ground felt increasingly irrelevant. Two bankruptcies later, the chain survives internationally while its American footprint has nearly vanished. The lesson? In a world demanding either cheap or special, being affordable but unremarkable leads nowhere.

5. Black Angus Steakhouse

Stuart Anderson’s 1964 creation brought Western charm to suburban shopping centers, complete with cowhide chairs and that all-important salad bar. Black Angus carved out a comfortable middle ground—nicer than fast food, more affordable than fine dining, and consistent enough that you knew exactly what you were getting in Tucson or Toledo. The formula worked so well that the chain survived two bankruptcies and keeps serving nostalgia alongside steaks.

Today’s 30-some locations prove that sometimes smaller is better, but only after learning expensive lessons about sustainable growth. Black Angus survived two bankruptcies by finally accepting that regional dominance beats national overreach. By focusing on Western states where the concept resonates most strongly, the chain found its sustainable size. It’s a rare success story demonstrating that knowing your limits can be more valuable than unlimited ambition.

4. Ponderosa Steakhouse

Named after the ranch from “Bonanza,” Ponderosa galloped onto the scene in 1965 with a simple proposition: unlimited buffet meets affordable steaks. Families descended like locusts on those sneeze-guarded spreads, piling plates high with everything from fried chicken to soft-serve ice cream. It was chaos and comfort food in equal measure, where picky eaters found salvation and parents found sanity.

The buffet model worked beautifully until food costs and health consciousness collided with operational reality. Maintaining quality across hundreds of buffet stations while managing rising ingredient prices proved impossible. Merged with Bonanza and eventually absorbed by FAT Brands, Ponderosa learned that high-volume, low-margin concepts are particularly vulnerable to economic shifts. Today’s scattered locations feel like time capsules from when all-you-can-eat meant guilt-free abundance.

3. Lone Star Steakhouse

Jamie Coulter’s 1989 creation brought Texas swagger to suburban America, complete with peanut shells covering the floor and enough neon to power a small city. Lone Star made dining feel like a honky-tonk party, where families could experience a sanitized version of cowboy culture between the appetizer and main course. The chain exploded to over 265 locations, proving that themed dining could work if you committed completely to the bit.

But theme restaurants face a unique challenge: gimmicks have expiration dates. As the novelty wore off and competition intensified, Lone Star couldn’t maintain its mystique or justify its premium over less theatrical competitors. Overexpansion into markets that didn’t embrace the Texas theme accelerated the decline. Most locations closed by 2017, proving that successful concepts must balance entertainment with sustainable economics.

2. Mr. Steak

Picture a family in 1975, sliding into vinyl booths where USDA Choice beef met budget-friendly dreams. Mr. Steak built an empire on the radical idea that quality steak shouldn’t require a second mortgage. Founded in 1962 by James Mather, the chain exploded to 278 locations, serving t-bones and sirloins with the reliability of a neighborhood diner.

But success bred the classic restaurant trap: brand dilution. Management’s pivot to “Mr. Steak, Seafood, and Salad” confused loyal customers who came for beef, not identity crisis. The lesson? Expanding your concept often means contracting your customer base. The last location closed in 2009, proving that sometimes doing one thing exceptionally beats doing everything adequately.

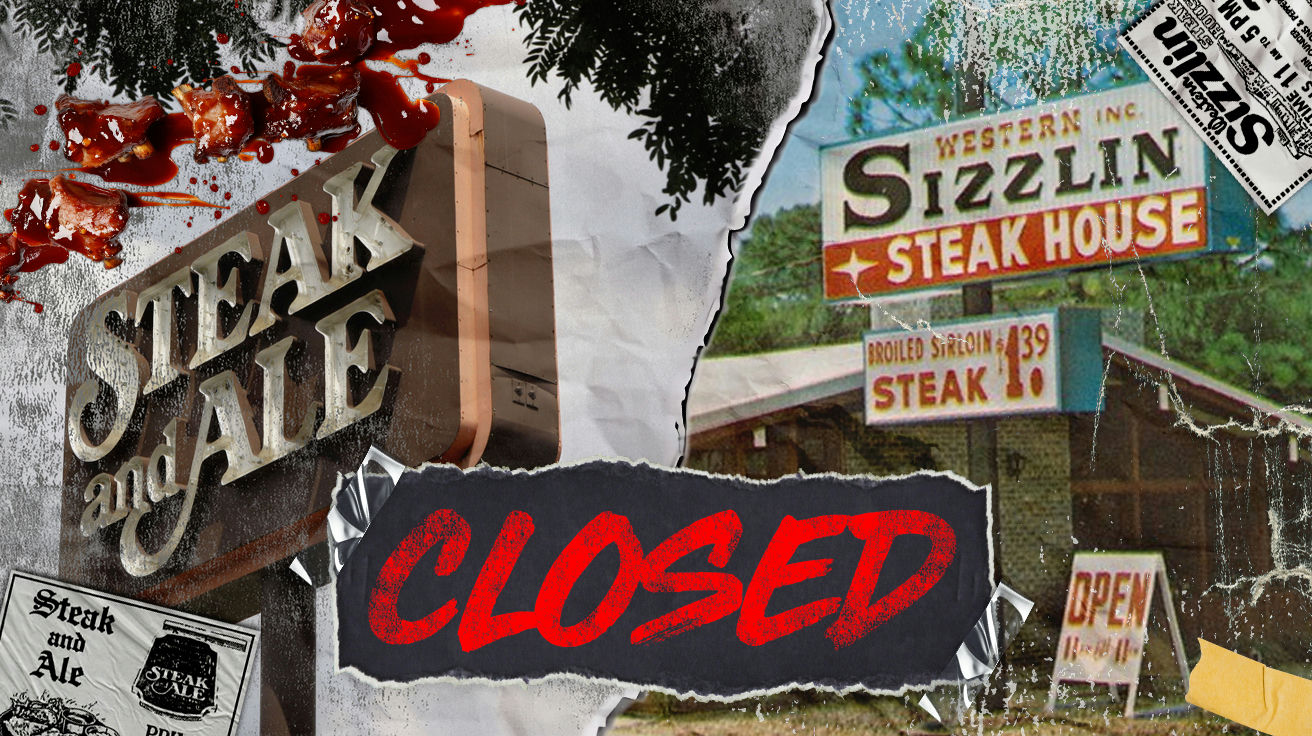

1. Steak and Ale

Before Outback made faux-Australian cool, Steak and Ale created Tudor-style magic in strip malls across America. Norman Brinker’s 1966 brainchild paired dim lighting with affordable prime rib, creating the template for casual steakhouse dining. Dark wood panels absorbed conversations about promotions and anniversaries, while that revolutionary salad bar let customers pile lettuce like they were preparing for nuclear winter.

The chain became a cultural touchstone—the place where first dates happened and business deals were sealed over affordable cuts of beef. But the very innovations that made Steak and Ale revolutionary—salad bars, casual atmosphere, affordable steaks—were eventually copied by competitors with deeper pockets and fresher concepts. The chain filed for bankruptcy in 2008, though recent attempts to revive the brand suggest nostalgia remains a powerful force in American dining.